Looking for a Forever Stock: Buy Big Oil

Super majors still dominate the world's indispensable industry as they have the last 150 years.

Editor's note: Thank you for reading Dividends with Roger Conrad. To receive my weekly posts automatically, see the links in the Substack application. Happy first day of autumn!—RC

In the 1975 sci-fi thriller "Rollerball," the late James Caan plays Johnathan E, superstar of a brutal game designed by the world's mega-corporation rulers to demonstrate the futility of individuality. His chief antagonist: The head of the "Energy Corporation," played by late John Houseman.

In the film, Houseman's character is first among equals on an uber board of directors. Energy is at the top—the indispensable industry.

Energy makes every other human endeavor possible. That means energy investors can always count on three things:

Perpetually rising demand over the long-term

A baseline of demand in even the worst economic circumstances

Perpetual incentives to find cheaper and cleaner ways to produce energy

The other basic truth about energy is it requires a great deal of capital. Achieving scale is a massive advantage for investment. And for 150 years and counting, the super major oil companies have been the biggest players by far.

Small oil and gas producers can offer more near-term upside potential. And a handful of companies—for example, EOG Resources (NYSE: EOG)—have grown into top oil and gas producers, enriching shareholders in the process.

But for steadiness and reliability of total returns, the super majors—that combine global oil and gas production with refining, distribution and midstream operations—have no peers.

Like all producers, these companies prosper most when energy prices are elevated and rising. But even with commodity prices slump as they did earlier this decade, super majors generate consistent cash flow. And that means they can pay robust dividends, while maintaining stronger balance sheets than many sovereign nations.

Energy downcycles also give the super majors the opportunity to become even more rich and powerful—by taking advantage of weaker and smaller rivals. and they've done so in recent years.

The two US super majors are Chevron Inc (NYSE: CVX) and ExxonMobil (NYSE: XOM). And there are three principal European supers as well. BP Plc (NYSE: BP) includes the former Amoco and ARCO and is practically as much a US as a UK company.

There's also Shell Plc (NYSE: SHEL), now headquartered in the UK after pulling up stakes in the Netherlands. And TotalEnergies (NYSE: TTE) is based in France, with operations around the world.

There was a time when super majors had control of the world's largest oil and gas reserves. That's now the part of national oil companies like Aramco and Petrobras. And Chinese oil companies like CNOOC—which is a partner with Chevron and ExxonMobil in the Stabroek field off the Guyanese coast— are increasingly rivals for major projects.

National oil companies, however, must always weigh their countries' interests ahead of shareholders. That's not the case for the super majors, including those like BP and TotalEnergies that still have some government ownership.

Super majors also lack government support when times are tough. But that too is an advantage, with management decisions constantly tested by the market and financial discipline a strict necessity.

That arguably makes these five companies the most flexible, financially powerful energy investors in the world. And they're now fresh off a wave of development and M&A that was mostly achieved at or near the low point in the long-term energy upcycle. So they're set up to be more profitable and dominant than ever as the up-cycle unfolds.

For example, Chevron's acquisition of Hess Corp this summer made the company a 30% partner in the Stabroek field off the Guyanese coast, now the world's most prolific expanding field. The lead owner and developer of that field is ExxonMobil, which became the leading producer from the Permian Basin buying Pioneer a year earlier.

The US super majors never stopped investing in oil and gas, even when "keep it in the ground" energy politics seemed unstoppable. So they have the reserves now to bring to market, as the combination of rising underlying demand and curtailed investment pushes up prices in coming years.

BP and Shell had pulled back exploration. And they've only recently begun shifting major resources back to oil and gas.

TotalEnergies is the exception. Management's strategy has been to split investment. Target one is growing oil and gas output at least 3% a year. And target two is to produce at least 100 gigawatts of renewable energy by 2030 with both development and acquisitions.

The company is succeeding at both. And power investments are now providing a rising stream of cash flow that's largely insulated from commodity price volatility.

All of these stocks also have two other things in common: They're under-owned and under-valued.

Let's start with weighting. Historically, oil and gas have averaged at about 5% of the S&P 500, considerably more at the peak of some energy up cycles.

Currently, the entire sector is barely half that weighting at 2.71%. And the largest energy stock—ExxonMobil—comes in at just 0.87%.

Now compare that to 37.14% of the S&P 500 that's in just 8 holdings: All Big Tech. Four of those stocks are weighted at more than twice the entire oil and gas sector.

Two reasons why this is important: One, there's now more money invested in S&P 500 ETFs than is actively managed. So being underweighted in the S&P 500 essentially means being under-owned across the board, and historically so. And two, everything in the stock market eventually reverts to the mean.

To paraphrase the legendary economist John Maynard Keynes, the stock market can remain irrational a lot longer than we can stay solvent. To that I would add there's no magic point where the S&P 500 must revert to some average level of historical balance.

But ultimately—as the Great Tech Wreck of 2000-02 taught all too many investors very painfully—funds will flow back to currently underweighted sectors including oil and gas.

As for value, super majors' dividend yields range from 3.5% to as much as 5.6%. And despite a weak year for commodity prices so far, those payouts are still increasing.

ExxonMobil will announce another mid-single digit percentage increase in November. Chevron (up 4.9%), BP (4%), Shell (4.1%) and TotalEnergies (7.6%) have already delivered boosts. TotalEnergies' payout in US dollar terms was further augmented by a 13.4% boost in the Euro.

Compare that to the paltry 1.1% trailing 12-month yield paid by S&P 500 ETFs, which varies widely from quarter the quarter. And the biggest oil and gas stock ExxonMobil sells for 16 times earnings, 1.6 times sales and 1.8 times book value. Those numbers for the largest S&P 500 stock NVIDIA (7.62%) are now 50.3, 25.7 and 42.9 times.

As with weighting, there's no magic point where valuations must revert to the mean. But again, conditions always change and balance is eventually restored.

Investing in energy now will put you on the right side when they do. And come what may before that, the super oils will keep you in the game for big gains.

I suggest a dividend reinvestment plan (DRIP). Every dividend paid buys you more stock. And that alone increases your income every three months, not even counting the super majors' ultra reliable dividend increases.

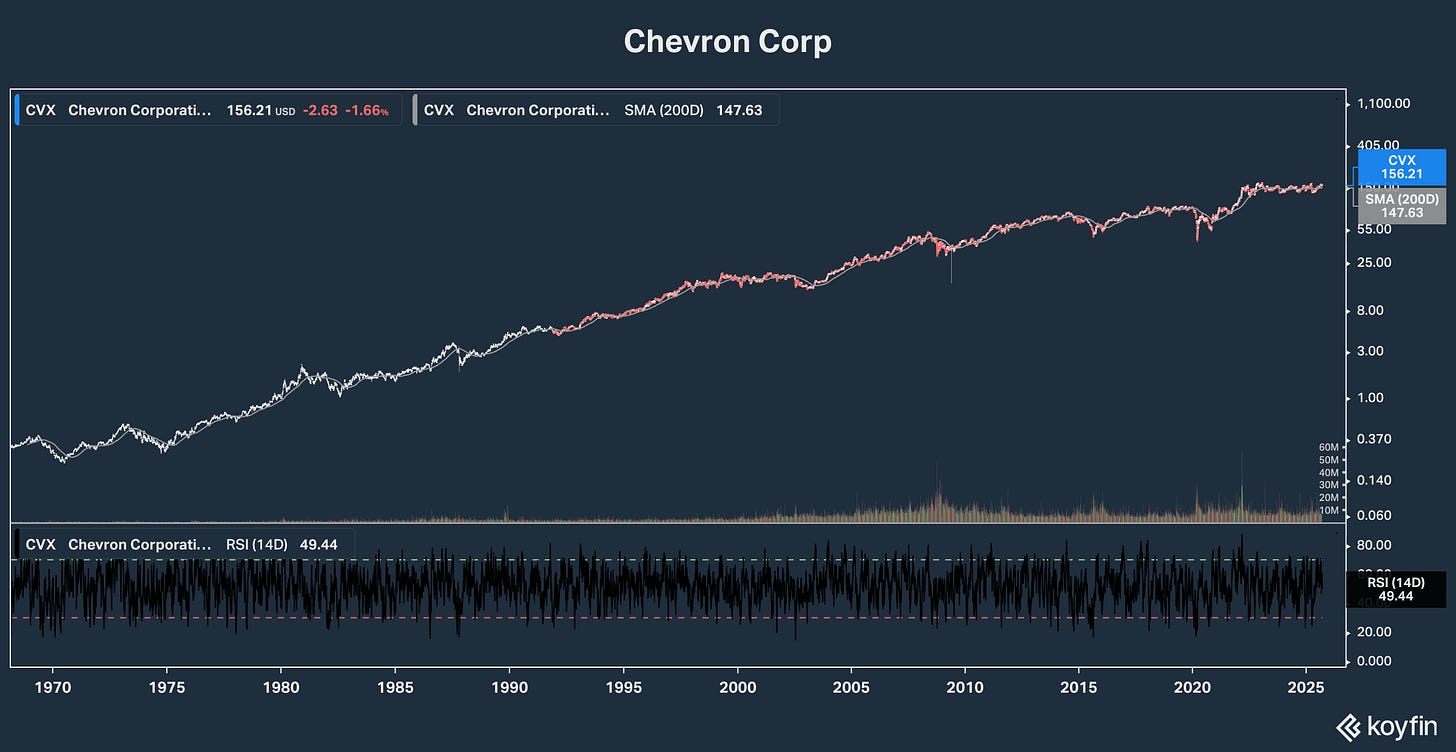

Let me close with a real life anecdote. I bought into Texaco's DRIP back in the 1980s. A few years later, that company merged to form super oil Chevron. And my DRIP now pays me more annually in dividends than my initial investment.

My annual income has already "lapped" what I first put into the company. And it's still compounding—even as Chevron's stock price has gained another 10% or so this year. That's what I call my money working for me!