Need Income? Buy an MLP!

Despite a poor reputation, MLPs pay safe yields of 9% and reliably build wealth.

Dividends Premium stocks have an average return of 30% plus so far in 2025. That’s more than three times the gain on the most popular dividend stock ETF—the iShare Select Dividend ETF (DVY).

I don’t say that to brag—just to make a point. You’ll get a lot more out of dividend stocks by thinking (and investing) a bit outside the box.

Don’t get me wrong. I like many of the stocks in the DVY. Altria Group (NYSE: MO), for example, pays a dividend yield north of 7 percent. And it recently rewarded shareholders with a dividend increase of 3.9 percent—not an earthshattering boost but still higher than the most recent inflation rate.

Altria is the third largest weighting in the DVY at 2.3 percent. I’m also a long-time shareholder of the number four holding, Edison International (NYSE: EIX) at 2.04 percent. The holding company for Southern California Edison sports a 5.6 percent yield, which it increased by 6.2 percent this year.

The stock is down more than -20% so far this year because of uncertainty about how much it will owe for the state’s wildfires last winter. But with liability capped at $4 billion by state law—and only assessable if the utility is proven negligent—I’m willing to bet the outcome here will be considerably more favorable than Edison’s current share price would suggest.

But I do have two major complaints with DVY. One is all the investment decisions are made by Dow Jones, which seems to be constantly fiddling with its U.S. Select Dividend Index to keep up with the S&P 500.

That’s the wrong benchmark for anyone who’s serious about dividends. And the proof is in the dividend yield: The SPDR S&P 500 ETF currently pays at rate of less than 1.1%. And while the DVY is somewhat higher at 3.4%, payments are erratic, ranging so far this year from $1.245 in September to as little as $1.049 in March.

Try counting on that to pay your bills! But my other objection is an even worse impediment to investor returns. Mainly, an ETF the size of the DVY is severely restricted in what it can buy and hold.

You’re not likely to know that unless you’ve had a role managing large funds. In fact, you might think that the more money a mutual fund or ETF has, the more investment options its managers have.

But the truth is precisely the opposite. The more money a fund has, the smaller the range of investments—stocks or bonds—that it can own in meaningful amounts, without literally becoming the market. And once that’s the case, it becomes impossible to exit a position in an orderly way, without having a huge impact on price.

To put this another way, say I run a $10 billion investment fund and want to hold 15 to 20 stocks. That’s a reasonable number, where each investment I choose could have a meaningful impact on returns. And if I choose well, I can produce superior returns for my investors on a regular basis.

To do that in a balanced way, I need to have $500 million or so in each stock. But if I target a company with $5 billion in market capitalization—a mid-cap stock—I’m going to wind up owning 10% of the company. I’ll be a major shareholder. I’ll have to file special documentation to that effect with the SEC. And you can bet I’ll have an audience of traders, ready to pounce should I try to make a fast exit.

To avoid being in that situation, my $500 million investment needs to be insignificant to the market capitalization of stocks I buy, preferably less than 1%. And that means sticking with companies of $50 billion or more, of which there are considerably fewer.

These are, of course, also the stocks all big funds and ETFs must buy from necessity. So by definition, it’s going to be very hard for me to make anything other than the average for the stock market’s largest companies. I’ll have plenty of Big Tech to choose from, as well as super oil majors and industrial icons like Ford Motor (NYSE: F), which not coincidentally is the largest holding in the DVY.

But I won’t be able to buy most stocks, including Dividends Premium companies that have been rewarding us with the biggest returns this year. And that includes most of the stocks with the biggest, safest and fastest growing dividend yields.

MLPs or “master limited partnerships” are nowhere to be found in the DVY. Nor are they in many large funds. And many individuals won’t go anywhere near them for fear of having to file a dreaded “Form K-1” with their taxes.

For investors, that’s basically the only significant difference between an MLP and a common stock: How the dividend is taxed. With a common stock, you (or your broker) receive a Form 1099 every year showing what part of your dividend is “ordinary” or “qualified.” And you’ll indicate that on your return, along with any other dividends received.

With an MLP, you receive a much more complicated form called a K-1, which contains a lot of information about the business and therefore takes more time to file with your return. But much of the dividend you received throughout the year is typically considered “return of capital.” That means no tax is owed until you sell.

The most absurd example of MLPs’ current unpopularity I can think of is the massive price difference between Brookfield Renewable’s NYSE-listed C-Corp shares traded under the symbol “BEPC” and its NYSE-listed partnership units traded as “BEP.”

Both are up a lot this year, as renewable energy stocks have emerged as some of the biggest winners during the first year of Trump Administration II. But as of Friday’s closing prices, a share of BEPC would cost you $13 or 46% more than a unit of BEP. That’s despite paying the exact same quarterly dividend and representing the same ownership of the company.

That’s a lot of K-1 fear. And you see the same thing comparing the prices of pipeline MLPs with pipeline C-Corps. MPLX LP (NYSE: MPLX) pays an 8% plus yield it this month increased by 12.5%. That compares to Williams Companies’ (NYSE: WMB) 3.3% yield that it increased 5.3% this year.

Will MLPs ever close this gap with C-Corps? Well, a decade ago pipeline MLPs actually traded at much higher prices and lower yields than comparable pipeline C-Corps. Investors valued the fact that taxes on MLP dividends were mostly deferred—in fact, they would never be owed if shareholders passed them onto their heirs.

MLPs’ premium reversed with a vengeance in the energy bear market that began in 2015 and finally ended in April 2020, with spot oil prices at some hubs in negative territory. Overbuilding and overleveraging during the boom times led to mass dividend cuts and worse across the MLP universe. And investors who had flocked to MLPs now fled, many vowing never to return.

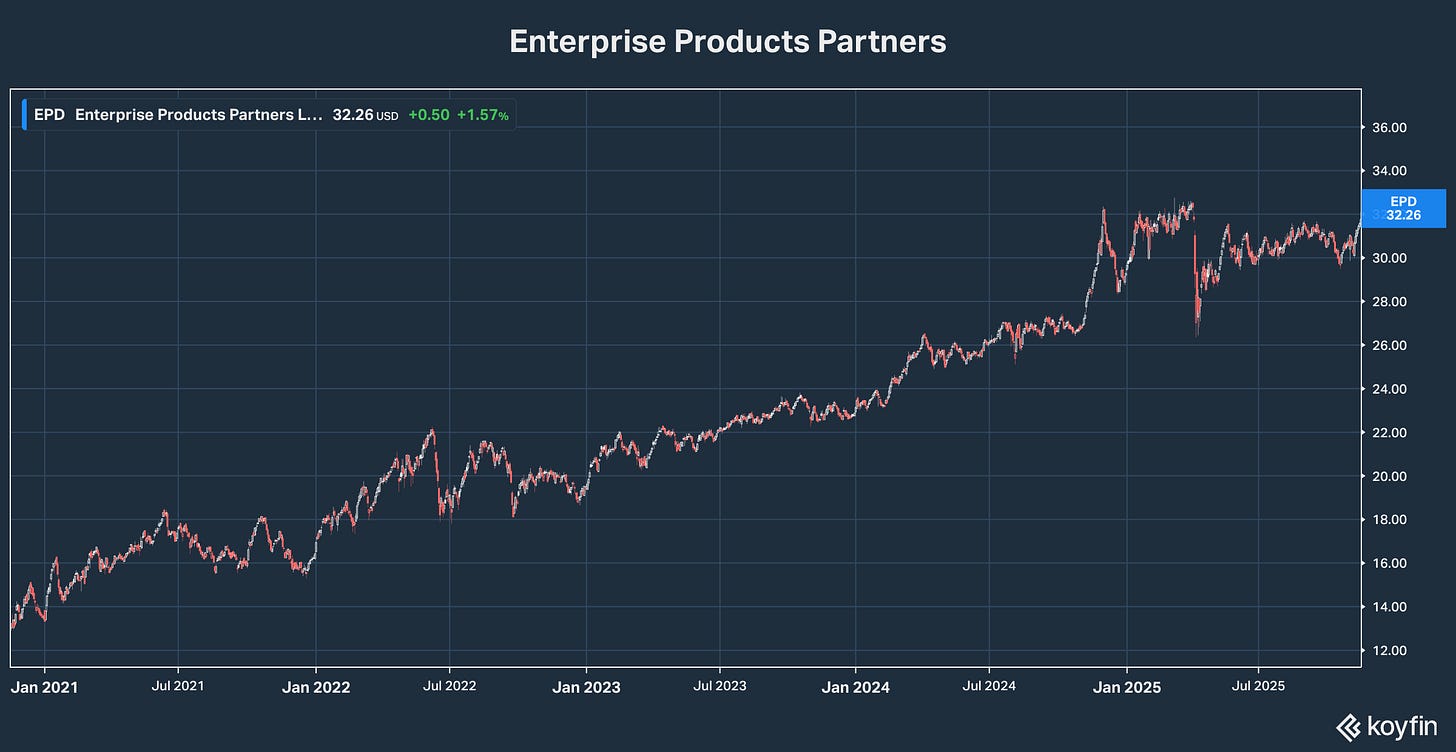

How has staying away worked out? Since mid-2020, shares of the sector’s bluest blue chip Enterprise Products Partners (NYSE: EPD)—which never once cut its dividend in the hard times—have roughly tripled. Ironically, it’s still a good time to buy them, trading almost -25% below what they sold for a decade ago. And they pay a dividend yield of nearly 7% that’s 23% higher than five years ago.

Bottom line: The MLPs still left are bigger and stronger than ever, having shed debt and risky assets. And they’re there for the picking, provided you’re willing to think outside the DVY/S&P 500 and aren’t afraid of a K-1.