Solar Plus Gas Vs Nuclear

Why politicians' favorite power source will remain a (highly) profitable niche.

Thank you for reading Dividends with Roger Conrad. If you like what you’re seeing, consider a monthly or annual subscription to my Dividends Premium service, including the Dividends Premium Income Portfolio, Dividends Premium REITs and exclusive access to my Dividends Roundtable hosted on Discord.

In this volatile stock market, more and more investors are discovering the power of reliable and consistently growing dividends—my specialty for the last 40 years. Here’s to your wealth (and fingers crossed for an early spring)!—RC

Fossil fuels are expensive and ravage the earth. Solar and wind are inefficient and propped up by failed liberal policies. And they aren’t really environmentally friendly either. Offshore wind kills whales and destroys fishing.

Query almost any energy source these days and you’ll find a host of criticism, arguing for “tougher” regulation, big fines for industry and even outright bans.

Only nuclear power seems to have a constituency on all sides of the political spectrum these days. And that’s high irony for those of us born in the middle of the previous century.

Mainly, for decades the environmental movement was fiercely united in opposition to nuclear plants, charging they could never be run without endangering everyone around them or that waste could be stored safely. Now, many of the same people embrace nuclear for not emitting CO2 causing climate change.

Understandably, few Republicans are talking about environmental challenges since the Trump Administration took office. But newly installed Department of Energy Secretary Chris Wright has already declared that “America must lead the commercialization of affordable and abundant nuclear energy.” And in his first order as secretary, Wright pledged to “work diligently and creatively to enable the rapid deployment and export of next generation nuclear technology.”

Small wonder then that investors have been bidding up prices of stocks like Oklo Inc (NYSE: OKLO), a nuclear development company that until recently counted Mr. Wright on its board of directors. And excitement has been further stoked by the interest of Big Tech companies in securing long-term contracts with nuclear power generators.

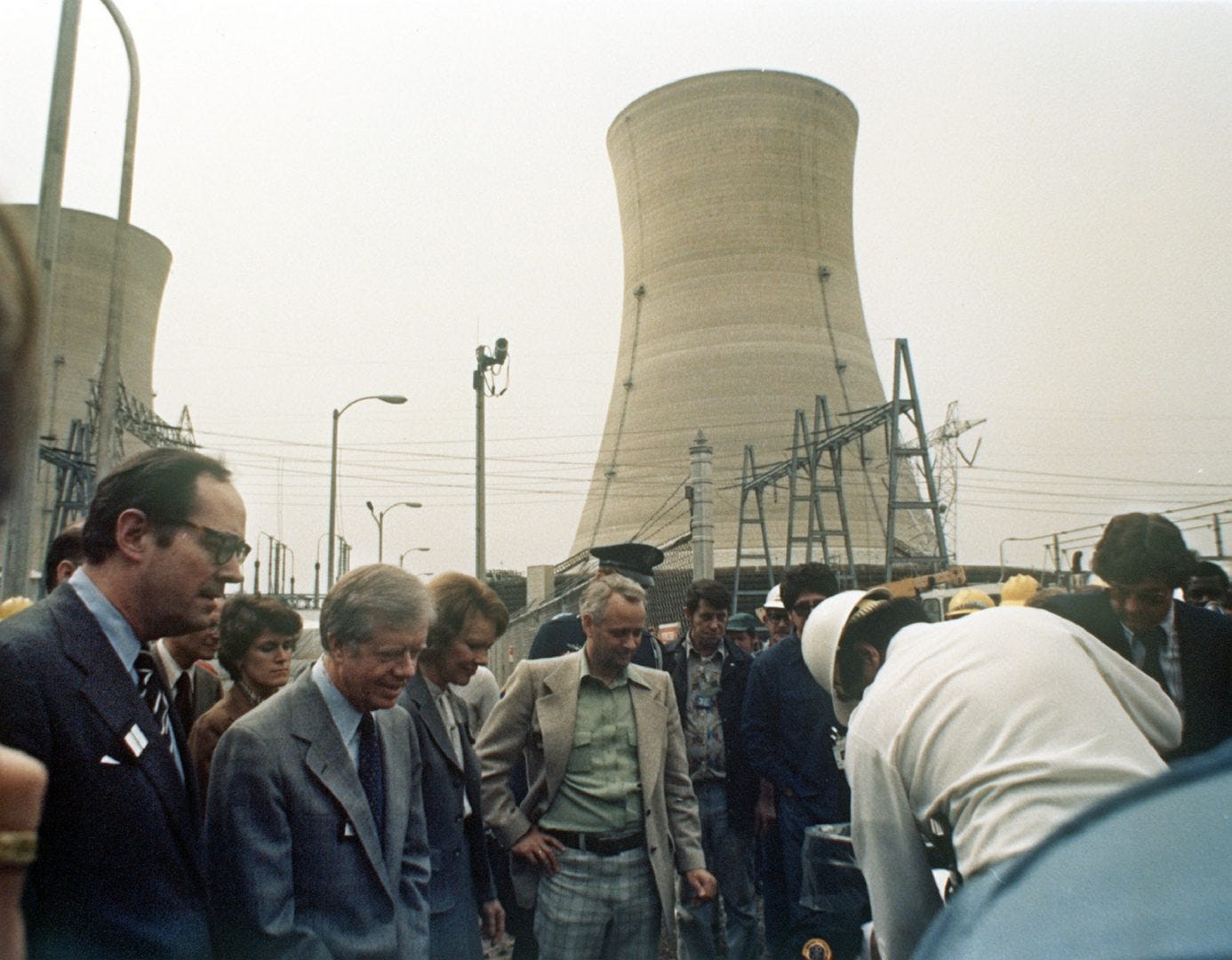

Constellation Energy (NYSE: CEG) announced last week that it’s on track to restart Three Mile Island Unit 1, shut in 2019, by 2028. There’s still work to do along with a hefty price tag ($1.6 billion) And anti-nuclear activists are suing to block it. But there’s also a pot of gold at the end of that rainbow: Microsoft has agreed to buy all the output from the plant under an above-market, long-term contract.

That’s quite a turnaround for a facility that ran at consistently high rates in its last years—95.65 percent in 2017—but didn’t come close to competing on price with electricity generated from cheap shale natural gas. And TMI 1 is even less competitive today on cost against a combination of natural gas and solar plus storage, which with some wind accounts for substantially all of America’s electricity generating capacity expected in come on line by the end of 2027.

The Palisades nuclear plant in Michigan may restart even faster than TMI. The plant was shut in 2022, when utility CMS Energy (NYSE: CMS) cut its costs by not renewing the power purchase contract with then-owner Entergy Corp (NYSE: ETR).

But new owner Holtec has since secured $3.1 billion in funding for a restart from the federal government, state of Michigan and grants to rural electric cooperatives. And NextEra Energy (NYSE: NEE) has filed a request with the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to restart the Duane Arnold plant in Iowa, which it closed in 2020 also for cost reasons.

The economics have clearly shifted in favor of restarting reactors. That’s in large part due to government support—first under the Biden Administration with generous Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) subsidy and now with Trump Administration assurances of more to come. And Big Tech is increasingly desperate to lock in long-term contracts with reliable pricing to run data centers.

In contrast, despite considerable financial incentives for R&D and new construction under the IRA, there have been no new orders for nuclear plants in the US for 20 years, including SMRs. Nor are there likely to be the rest of this decade, even in a best case.

When the Biden Administration incentivized solar deployment including re-shoring of manufacturing, it was leaning into something the private sector was already doing. But since Southern Company (NYSE: SO) successfully brought two new AP-1000 reactors into service at the Vogtle site in Georgia a year ago, it’s been crickets for new nuclear. That’s other than some very low cost “exploratory” efforts included in long-term supply plans by large southern utilities like Dominion Energy (NYSE: D) in Virginia.

Dominion also operates the Summer 1 nuclear plant in South Carolina, acquired with the SCANA merger in the previous decade. But during the company’s recent Q4 earnings call, management disavowed any interest in reviving suspended construction of AP-1000 reactors Summer 2 and 3. That’s basically the same language we’ve heard from executives at Southern Company when asked about new nuclear construction post Vogtle 3 and 4.

Southern intends to upgrade Vogtle units 1 and 2 to produce more, largely by replacing non-nuclear components at the facility. And that in turn mirrors efforts announced at other nuclear utilities and America’s leading nuclear generator Constellation Energy. But that company too is devoting its efforts to upgrades and restarts, while just paying lip service to new construction.

Why the reluctance to build new nuclear? The main reason is there’s no way right now for a developer to give believable assurances on ultimate costs to investors and regulators. And that goes for SMRs just as much as large units like the AP1000, which are now operating all over the world.

Nuclear advocates—both in mainstream media and opinion forums like X—blame permitting times. That’s fair to a point.

AP1000 projects like Southern’s especially went through the wringer following the 2011 Fukushima accident in Japan. That alone made it literally impossible for EPC (engineering, procurement and construction) companies like Toshiba Westinghouse to fulfill the fixed priced contracts they’d signed. And their bankruptcies triggered delays and massive cost overruns.

Streamlining permitting, however, will only go so far. In fact, if done too aggressively, projects could become impossible to insure economically. And delays from court challenges would easily wipe out any time saved from cutting red tape.

I would expect siting to be less of an obstacle than in the past. That’s mainly because utilities and other generators can build on their existing sites, which already have supporting infrastructure including roads, buildings and grid connections.

But as the Vogtle project demonstrated, there are few if any shortcuts to time needed for actual engineering, construction and pre-start testing. And as a result, even the most aggressive projections for start to finish nuclear plants are in the 10-year range—Vogtle wound up taking close to 20.

Try projecting costs for a project still in progress a decade from now. Then add on the fact that there is still no commercially proven model for SMRs. And what you have is an insurmountable economic gap between nuclear and the currently dominant mix of solar, battery storage and natural gas generation that now accounts for almost all new US construction.

New solar, battery storage and on-shore wind can right now be planned, sited, permitted, procured for, built, tested and opened in 12 to 18 months. Natural gas in most parts of the US takes 3 to 5 years and an EPC shortage has pushed up all-in costs to twice what they were 2-3 years ago. But even so, that’s less than half the time needed for nuclear. And gas’ predictable, unsubsidized costs are a tiny fraction of what it takes to build new reactor.

I believe in scientific breakthroughs—but only if there’s enough money trying to find them for long enough, and better solutions don’t emerge in the meantime.

With energy, investors are always best off betting on companies that are making money now. The hype about what could be dominant in 5 to 10 years—only if everything goes as planned or better—is best taken with a large grain of salt.

America’s electric power industry would clearly love to build more nuclear at some point. But right now, demand is growing in real time at the fastest pace since the 1960s. And it’s not just from data centers. It’s also historic re-shoring of manufacturing, still growing electric vehicle adoption, industrial and buildings electrification and population growth.

Bottom line: Power companies must build to meet fast materializing demand in the most economic way. And that may or may not be what politicians and advocates prefer.

Currently operating nuclear plants along with restarts of recently shut reactors fit the bill. And they occupy an increasingly valuable niche in the current energy market place. But at a time when everything depends on deployment speed and predictable costs, new nuclear just doesn’t come close to competing with solar and gas.